In distributed and concurrent systems, linearisability (also called {atomic, strong, immediate, external} consistency) is the idea that a system should appear as if there was a single version of data, i.e., it should behave like a single-threaded system, where all read/write operations are atomic, and where all clients read the value of the most recent write.

i.e., we write 3, read 3. If we write 3, write 2, read 3, the system isn’t linearisable.

It is a data consistency model that tries to match our expectations (as programmers) of storage behaviour. It takes concurrent operations into account, and is independent of the system’s details (network, timing model, replication).

Linearisation doesn’t only apply to reads/writes. It can also work for deletes, appends, increments, atomic compare-and-swaps. The main downside of linearisability is that is limits parallelism by enforcing a serial timeline of operations.

This consistency model has the lowest performance and highest latency (since every request requires communication with a majority/quorum of replicas). It also has low availability, when nodes are down.

Construction

The motivation behind this is:

- Concurrent operations result in an unclear order of events (given multiple writes and multiple reads, which version of the data do we return?).

- Best-effort links lose, duplicate, or reorder messages (like

ack). - Nodes can crash and lose data on recovery.

- Data is replicated across nodes, meaning it may not be synchronised.

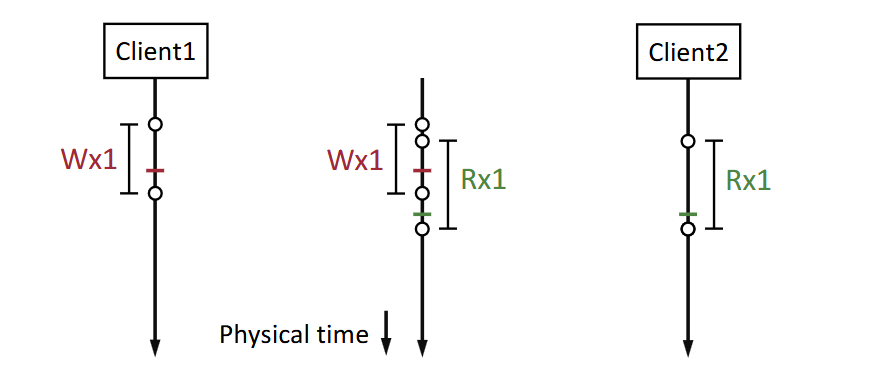

A history is defined as a trace of possibly concurrent operations. Each operation is an RPC with an invocation (with arguments, from the client), and a response (with result values, like an ack). This creates a timeline of events, where each event has a physical time duration (from invocation to response time). This history is from the POV of the clients, and the storage system (server) is a black box.

A history is linearisable if every operation in the history takes effect (i.e., appears to execute) at some point instantaneously between its invocation and response. In other words:

- We can find a point in time for each operation (a linearisation point) between its invocation and response.

- The result of every operation is the same as serial execution of the operations at their linearisation points. Thus, we can create a timeline.1

Then, with linearisability, we have the following properties:

- Operations appear to execute in a total order.

- Total order maintains a real-time order between operations.

- i.e., if A completes before B begins in real-time, then A must be ordered before B.

- If neither A nor B completes before the other begins, then there is no real-time order, but there must be some total order.

The implication of this:

- Clients see the same order of writes.

- Clients read the latest data.

- Once a read returns a value, all following reads return that value (or some later write).

- i.e., clients won’t be reading from a stale cache or replica.

- In summary, the application won’t need to worry about multiple replicas.

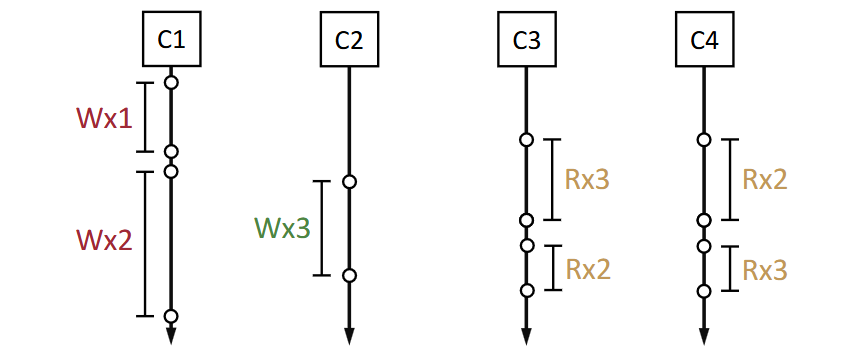

We may need to formulate a set of linearisable operations. Some tips:

- We can’t tell in advance which results will be returned.

- We need to beware which operations have a total order. For example, the below is not linearisable because C3/C4 conflict:

Implementation

In practice, a single server implementation (without replication or some caching schemes) can implement linearisability quite easily. It needs to ensure exactly-once semantics (i.e., each operation happens exactly once).

- Duplicate operations won’t guarantee linearisability. Suppose a duplicate operation arrives after many operations, but we thought it was linearised earlier (so get a wrong final result).

- So we need to check for duplicates, perhaps by assigning an ID to each RPC.

- The server needs to store all updated data durably on disk.

- Otherwise we lose an idea of what ordering we have upon a crash.

- All updated data must be stored atomically so it can be recovered correctly on crash failure.

- This maintains linearisability’s guarantee. Either the data is written fully, or not at all. If it’s written partially, we lose the ability to reason what kind of ordering we have.

- An alternative to the above two is to use a fault tolerant service.

Footnotes

-

Diagrams from Prof Goel’s lecture slides. ↩