Raft is a consensus algorithm that uses leaders to implement fault tolerant state machine replication. There are several key components to its specification:

- Leader election: nodes will elect one leader at a time.

- Log replication: leader broadcasts messages to replicas in order.

- Crash recovery: handles crashed replicas.

- Log compaction: discards obsolete log entries.

- Client interaction: ensures exactly-once semantics.

It implements a linearisable consistency model. This partly means that its performance is fairly poor relative to other distributed tools (possibly with weaker consistency models). The relative performance for Raft increases for read-heavy systems (intuitively, write-heavy systems will need to do expensive replication operations).

Leader election

Raft divides the timeline into multiple terms (or epochs). Each term begins with a leader election initiated by candidate node(s). If an election fails, a term has no leader. Otherwise, a term has one leader that performs log replication. Each node maintains their own view of what the current term is (no global view). This current term is exchanged in each RPC, so that if a server sees a term greater than itself, then it updates itself and becomes a follower. And eventually all terms will converge on the latest value. Terms essentially act as a logical clock.

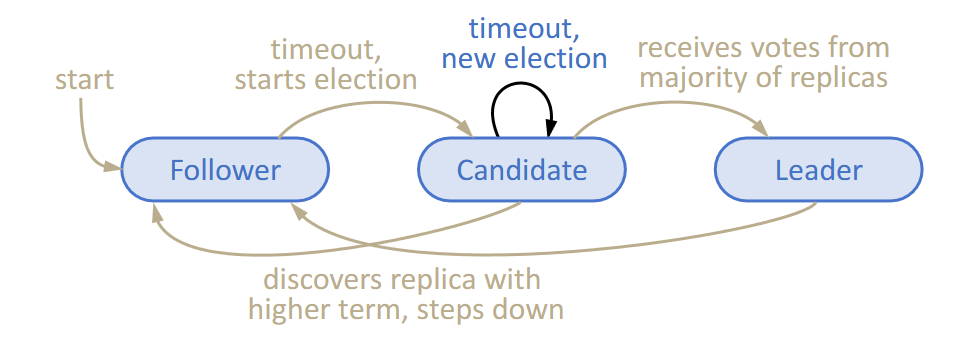

Each replica is in any one three states:

- Followers receive messages from the leader. They’re passive, but expect regular heartbeats.

- Candidates start an election to try to become the new leader.

- Leaders handle all client interactions and perform log replication.

Heartbeats are sent periodically by the leader. These use the

Heartbeats are sent periodically by the leader. These use the AppendEntriesRPC with an empty append log. Heartbeat timers should be a single deterministic, fixed periodic value. When a follower has received a heartbeat, they should reset an election timer. This timer is random within a range greater than the heartbeat timer (the randomness ensures election conflicts get resolved eventually, if they happen at all).

On system start-up, all nodes in the network will be in the follower state with some election timeout. The first node that times out will initiate an election and possibly become the leader, after which it sends periodic heartbeats to maintain authority.

When the timer has timed out, the follower will transition to a candidate and initiate an election, with the assumption that the leader has crashed. It starts the election by incrementing the current term, changing its state, and voting for itself. Then, it sends a RequestVote RPC to all other replicas. There are three possible outcomes:

- A candidate will win the election if it receives votes from a majority of the servers in the full cluster (i.e., this includes dead nodes). Each node can cast at most one ballot for a given term (if it sees a node with a higher term, then it resets its vote status). This ensures that there is only one leader at a time.

- Or, a candidate may receive an

AppendEntriesRPC from another node that claims to be the leader. If this RPC is legitimate, i.e., the received term is higher than itself, then the node will transition back to a follower node (and the election should fail). - Or, the candidate neither wins nor loses the election. This can be caused by multiple nodes entering an election state at the same time. Since nodes vote for themselves, it means that no node will cast an affirmative vote. In this case, each candidate times out and will start an new election. The randomised timeouts ensure that split votes are resolved quickly and are relatively rare.

One problem is that we don’t really know whether entries in a given node are committed during elections (what if data is committed, then multiple nodes crash, and another node with a longer log tries to become leader?). We add an additional restriction where a candidate can only become leader if it has all potentially committed entries. Replicas vote yes if the candidate’s log is at least as up to date, i.e.,

- If has a higher term in the last log entry.

- Or the candidate has the same last term and same or longer log length.

So servers aren’t elected leaders if they don’t have all committed entries. This design ensures that:

- At least one server (the one with the most up-to-date log) will always be eligible to become leader.

- Once elected, this leader can then replicate any missing entries to other servers.

Consider a 5-server cluster where entries have been partially replicated:

- Server 1: [1,2,3,4,5] (most complete)

- Server 2: [1,2,3,4]

- Server 3: [1,2,3]

- Server 4: [1,2]

- Server 5: [1]

If all servers are alive, Server 1 can get votes from itself, Server 2, and Server 3 (assuming they haven’t voted for someone else in this term), forming a majority. Then as leader, it replicates the missing entries to the followers.

Log replication

Each log entry stores a few bits of information: the term number that the leader had when it appended to its log, and the operation. Each entry is also indexed (much like an array index). Log replication is used to broadcast client operations in FIFO-total order and ensure that the logs can remain consistent.

In regular operation:

- The client will send commands to the leader.

- The leader will append the command to its log (including durably on disk), and the leader will send

AppendEntriesRPCs to all its followers. - An entry is committed if it’s safe to execute in state machines. In other words, it’s committed if an action is logged by a majority of nodes and restriction #2. The leader learns an operation is committed when it receives acks from a majority of nodes (including itself).

- Replicas will only deliver committed operations to the service.

- Restriction #2: a leader decides an entry is committed when at least 1 new entry from the leader’s term is also in the majority. Basically, the commit is always 1 behind the leader.

- The leader’s service (which wraps on top of the Raft library) will update its state and acknowledge the client’s operation.

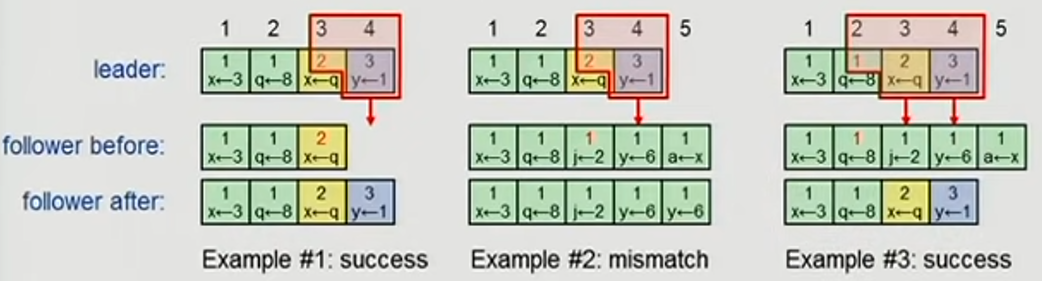

Crashes can result in log inconsistencies. Raft doesn’t really use too much logic for repairing inconsistencies. The leader will assume its log is always correct, so followers will have to synchronise with the leader’s log. The log matching properties are always maintained:

- If two log entries on different replicas have the same index and term, then:

- They store the same operations.

- Logs are identical in all preceding entries.

- If a given entry is committed, all preceding entries are also committed.

On each AppendEntries RPC, it should include the <index, term> of the entry (not the operation!) preceding the new one. The follower must contain the matching entry, otherwise it rejects the request. If a request is rejected, then the leader will send another previous entry further away (see examples 2/3) below. This is basically an induction step, and the core idea is that we don’t know where the divergence has occurred so we keep trying until we get something that works.

The leader knows an entry of a current term is committed when it is stored durably on a majority. Then, the leader in the next term must contain that entry. Nodes without that entry cannot be elected.

Crash recovery

Raft can continue operation provided a majority of nodes continue to run. Once more than that happens, we run into unavailability problems. Raft allows for a crash-stop and crash-recovery model. Each replica will store the following state on disk:

- Logs: stores committed (and tentative) entries.

- If committed entries are lost by a majority of replicas, then they could be forgotten by a leader in a later term.

- votedFor: the candidate the replica voted for in the current term. This just ensures that on crash, it doesn’t revote for a different leader in the same term.

- currentTerm

Log compaction

Core idea is that it’s too expensive (space) and slow (time) to save the whole log on disk. Crash recovery also means that the entire log on disk is replayed (lots of time), and the leader will have to send the entire log to the new server (again takes lots of time).

Thus the log can be larger than the service state, but clients only see the client state. So instead, we keep a snapshot of the service state, and only keep the tail of the log after the snapshot (everything saved on disk has been applied). This snapshot basically only keeps what is essential:

- Term, index

- State values at snapshot time (actions that have been completed!). This is enough to restore state without saving everything, because you basically only save the useful actions that haven’t been overwritten yet.

Client interaction

If we assume a linearisable consistency guarantee, then read-only operations cannot be issued to any follower (since followers may lag leaders). In this case, when a leader receives a read-only operation, it sends heartbeat messages to followers, waits for a majority (to see if it’s still the current leader), then responds to read-only operations.

If a client sends an operation to a follower, it will respond that it isn’t the leader. There are a couple of ways around this. The client could keep retrying with different servers, then cache information about the leader. The node could also cache info about the leader and may tell the client to request another node that is likely to be the leader.

Resources

- Original resources by Diego Ongaro and John Ousterhout

- In Search of an Understandable Consensus Algorithm (Extended Version)

- Designing for Understandability: The Raft Consensus Algorithm, Distinguished Lecture by John Ousterhout at UIUC’s School of Computing

- Labs

- ECE419 — Distributed Systems at UofT

- 6.5840 — Distributed Systems at MIT