IPv6 is one of two main versions of the Internet Protocol (IP), the other being IPv4. It is the newer of the two, and was designed to address problems with IPv4:

- IPv4’s 32-bit address space was completely allocated. IPv6 addresses this with 128-bit addresses.

- There’s a 40-byte fixed length header, already smaller than IPv4 and non-variable.

- It is designed to enable different network layer treatment of “flows”, i.e., like a connection-oriented abstraction. IPv4 was designed with a datagram-oriented abstraction.

In general, IPv6 has seen a great deal of adoption. However, NAT in general has made the switch to IPv6 much less critical.

Specification

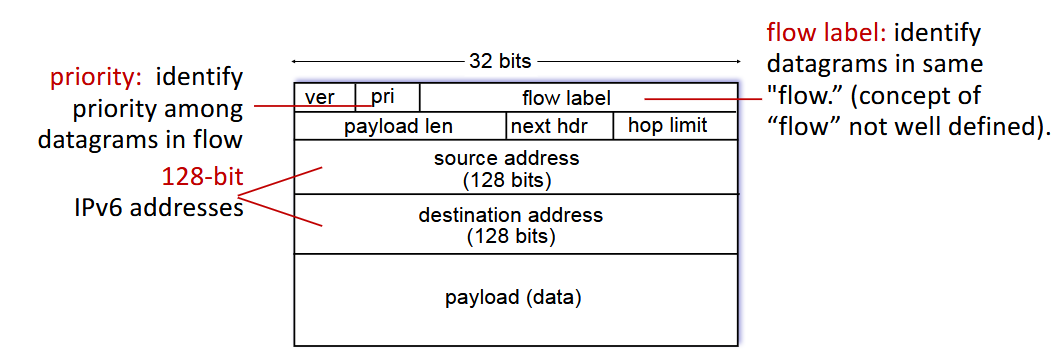

The IPv6 datagram is below:

What is the same as IPv4:

What is the same as IPv4:

- Versioning number

- Next header

Note what is missing compared to IPv4:

- No checksum, to speed-up processing at routers.

- No fragmentation/reassembly. It is instead done at the endpoint.

- No options. We can instead pass it as a payload.

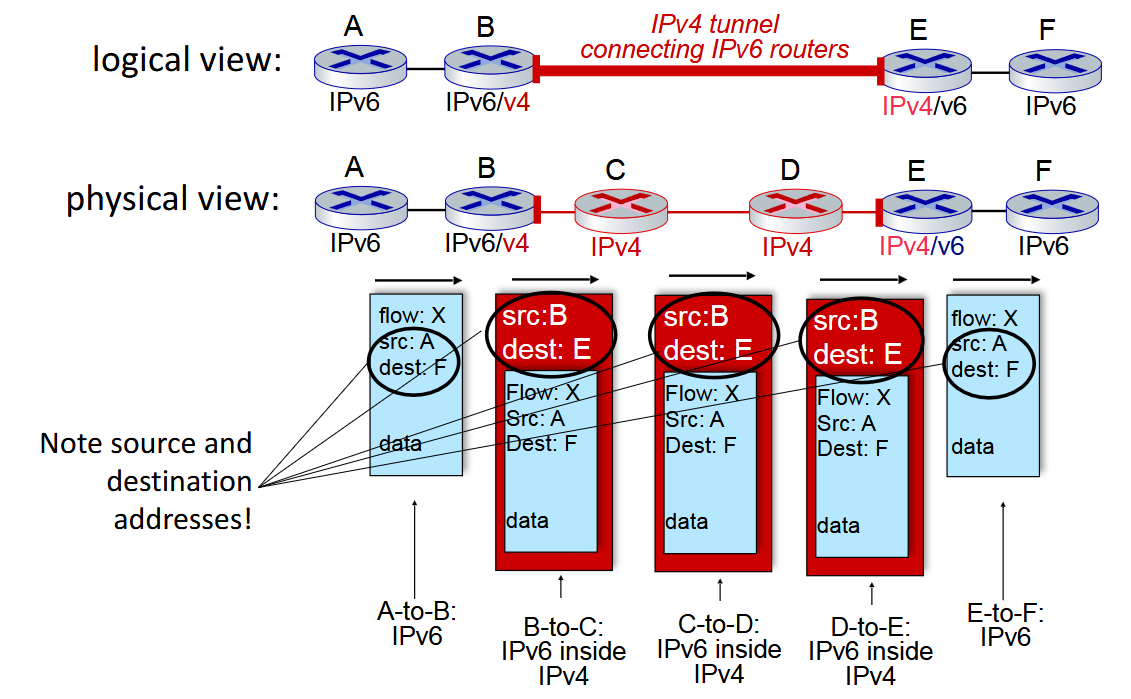

Tunnelling

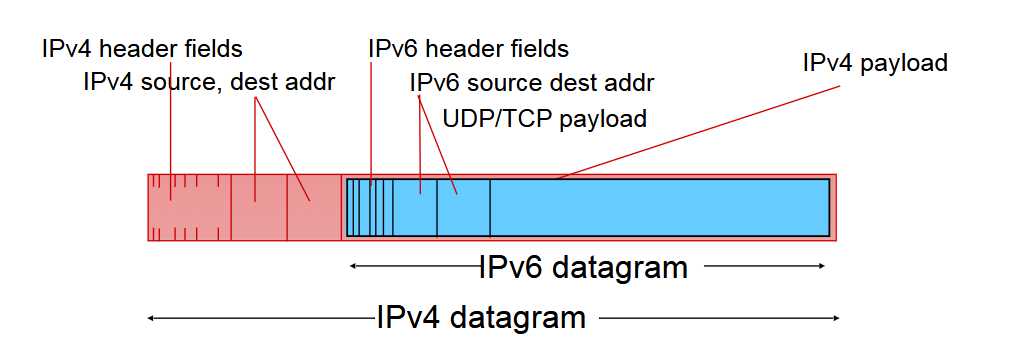

Not all routers can be upgrade simultaneously. Routers operate with mixed IPv4 and IPv6 datagrams via tunnelling, where IPv6 datagrams are carried as a payload in an IPv4 datagram among IPv4 routers (a packet within a packet). This idea is also used in 4G/5G.

In a solely IPv6 subset of the network, the datagram is as usual (plus the link layer frame). In a mixed IPv4/IPv6 network, we might need to send a datagram between two IPv6 datagrams via an IPv4 subnet. In this case, we tunnel the IPv6 datagram within an IPv4 datagram. In this sense, the IPv4 basically functions like a link layer technology.

In a solely IPv6 subset of the network, the datagram is as usual (plus the link layer frame). In a mixed IPv4/IPv6 network, we might need to send a datagram between two IPv6 datagrams via an IPv4 subnet. In this case, we tunnel the IPv6 datagram within an IPv4 datagram. In this sense, the IPv4 basically functions like a link layer technology.