The eye is the primary biological optical organ. It’s useful as an analytical tool in geometric optics.

Construction

It’s made up of a few constituent components:

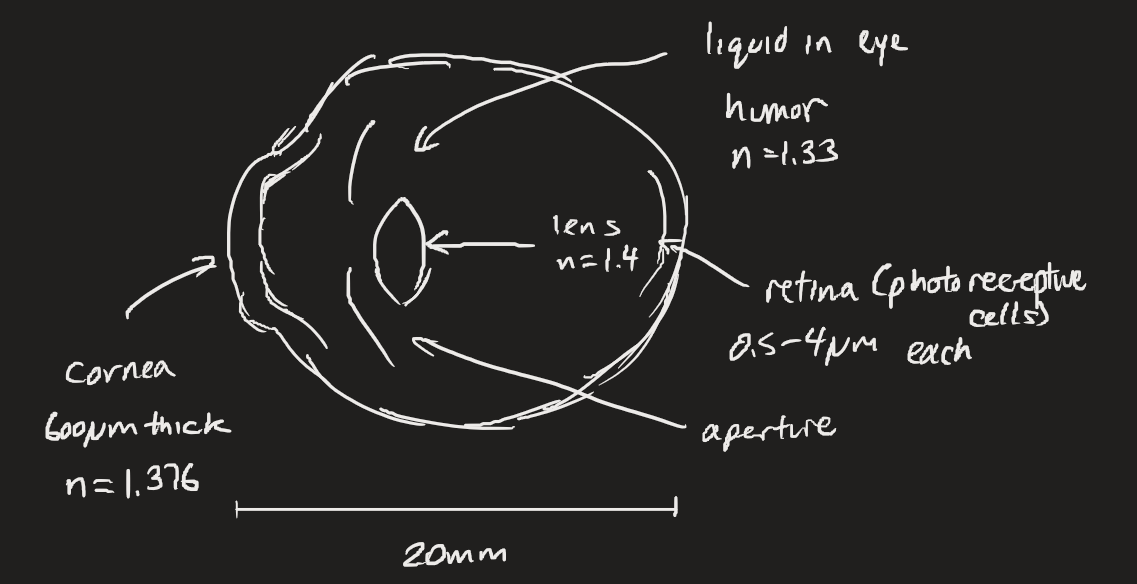

- The eye itself is around 20 mm wide.

- The cornea is at the surface of the eyeball. We approximate it as a spherical boundary between two interfaces.

- There’s a lens inside.

- The eyeball is made up of a liquid called the humor.

- There’s also an aperture, the opening of which is called the pupil.

- And the retina, which functions effectively as an imaging sensor. It contains photoreceptive cells (cones and rods).

The eye is capable of a few key acts:

The eye is capable of a few key acts: - Adaption — control of the pupil size.

- Accommodation — adjustment of the lens’ focal length.

A few parameters associated with our vision:

- Object focal length — is around 12 mm. It varies as the eye accommodates, but not by too much.

- Near point — nearest position of distinct vision. For a healthy eye, we take it as .

- In other words, an object at the near point is at . This results in a specific image distance .

- If we add corrective lenses or contact lenses, this is fixed and we find a new .

- Far point — furthest position of distinct vision. For a normal eye, we take it as .

Conditions

Common conditions associated with the eye:

Common conditions associated with the eye:

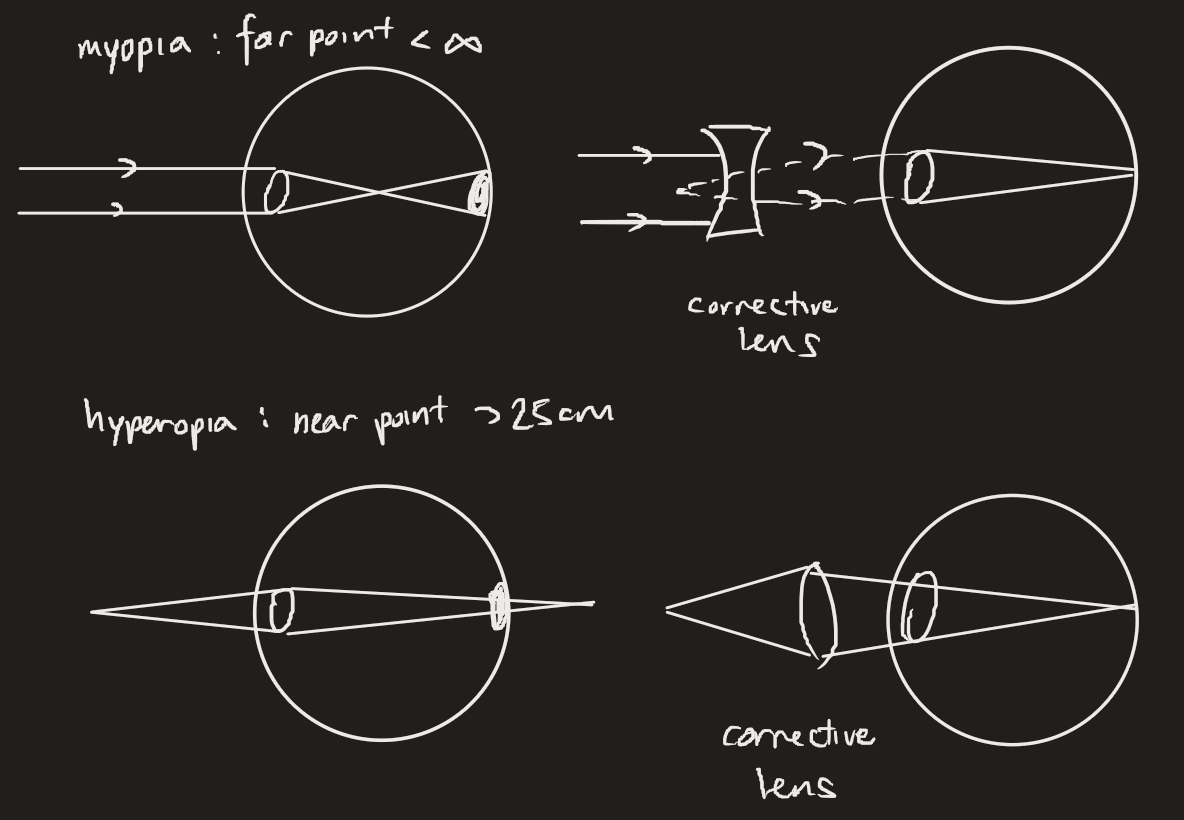

- Myopia (near sightedness) — where the far point is less than . The result is that it creates a blur, since the rays don’t converge on the retina.

- We correct with a divergent lens (concave lens), such that the lens creates an upright virtual image (closer than the real object) that the eye treats as a real object.

- Hyperopia — where the near point is greater than 25 cm.

- We correct with a convergent lens (convex lens). The lens creates an upright larger virtual image further away from the eye than the real object.

- Astigmatism — where the cornea is asymmetric, i.e., . We correct with cylindrical lenses.