In economics, we differentiate between several types of costs.

Life cycle costs

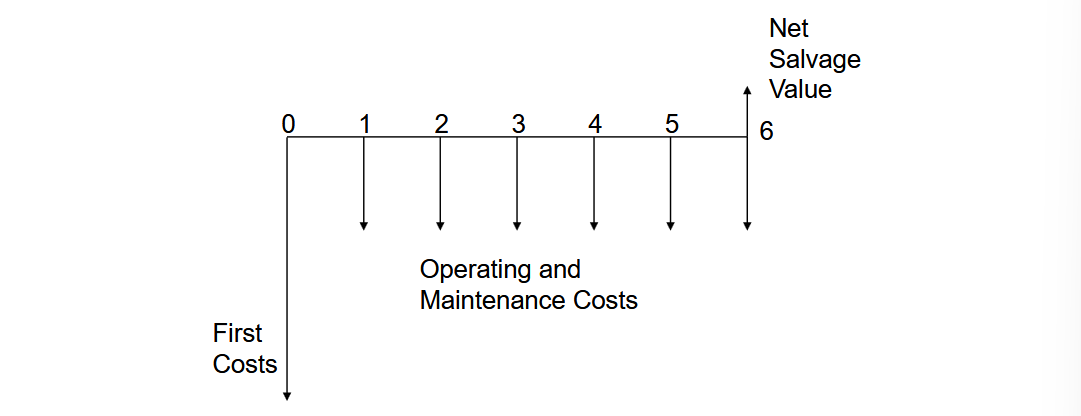

Life cycle costs are the sum of all expenditures associated with the project during its entire service life (cycle). There are a few constituent costs:

- Acquisition (or first) costs (FC) — usually happen at the start of the project.

- Includes: purchase price of item, shipping and installation, training costs, and supporting equipment costs. i.e., getting it installed.

- Operating and maintenance costs (OM) — labour, material, and overhead items. These are recurring costs. Overhead items include fuel, electricity, insurance premiums, etc.

- Disposal costs — at the equipment’s end of life. Mainly involves any specialised labour or material costs for removal and shipping of the item.

At disposal, the item will have a market/trade-in value. We’ll be able to get something back.

Salvage value (SV) = market value - disposal costs

Generally, machinery, equipment, buildings, and other fixed assets gradually decrease in value. This is because they physically deteriorate or because of obsolescence. This loss of value is an additional part of the operating cost called depreciation. We essentially assign a fixed amount yearly called a depreciation charge that is added to the annual operating cost. Note that this isn’t an actual cash flow.

We define the capital cost:

as on average, how much does it cost us to own this equipment, where is the number of years we own the equipment.

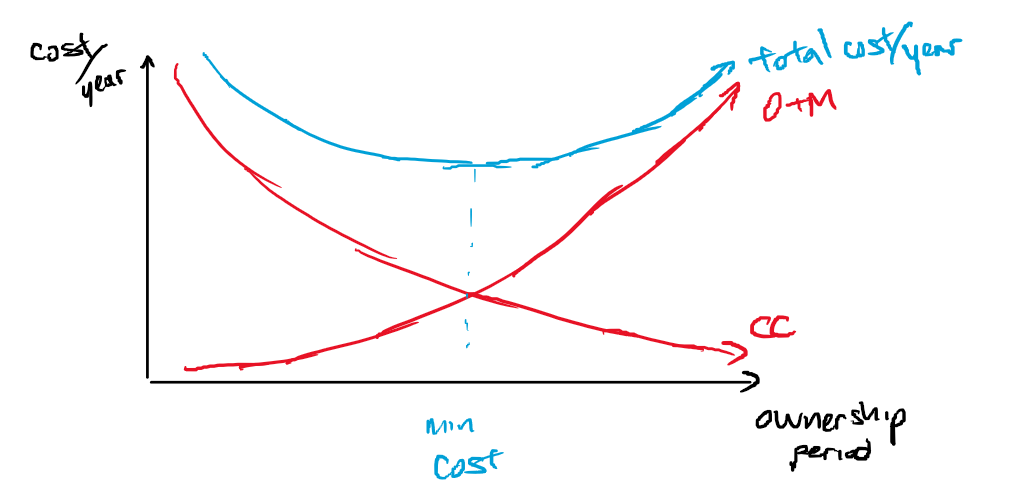

Note that in general maintenance costs go up over year, because the equipment will deteriorate. The capital cost decreases, because of the time value of money. Then the total cost per year is the CC + OM cost. We want to minimise the cost we pay. Not necessarily at the curve intersection:

Lifetime

To be able to fairly compare alternatives, we have to compare all the costs over the life of each alternative, i.e., the ownership period.

- Functional life — maximise time. This is the amount of time that an item can continue to be used for.

- Economic life — minimise cost. This is generally shorter than the functional life. This is the estimated life we use for engineering analysis.

- i.e., when computing the yearly depreciation charge (see above), we take the difference between the first cost and the salvage value, then divide by the economic life.

For example, a laptop may be usable for 15 years (functional life), but general improvements in hardware technology may mean it’s economically useful for only 5 years (economic life) because of obsolescence.

Historical costs

We define past costs as historical costs that have occurred for a given item. Then, we define sunk costs as past costs that are unrecoverable (i.e., no refund, cannot be recouped). The main important part about our analysis is that sunk costs shouldn’t influence our decisions, because they’re unrecoverable. This means that if we’re mid-project, the only thing that should influence how we assess alternatives is their future benefits and future costs.

Product costs

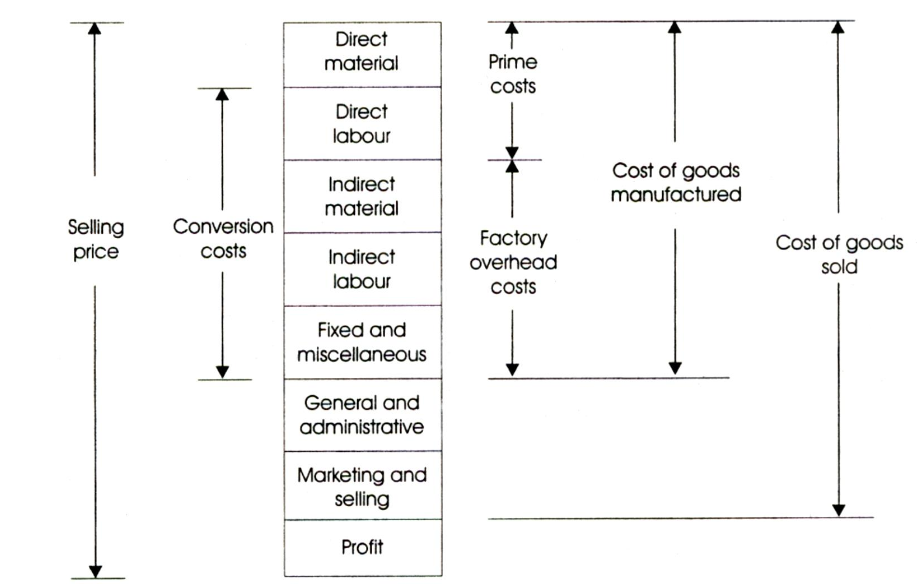

These costs help us determine the sale price of a product:

- Direct costs mainly consist of material and labour costs. These are easily measurable and conveniently allocated to a specific project.

- Indirect costs consist of material and labour costs that are practically impossible to attribute to a specific project.

- Overhead costs are all other costs than direct (material/labour).

When determining the cost of a product we’re selling, we need to make back the cost per item produced. We do this by distributing the indirect costs to the amount of items we make (i.e., if we make 50k chips, and maintenance for the plant is 50k, then each chip has a maintenance cost of $1). We then sum the total indirect and direct costs to get the base cost.

We also add a desired profit margin on top of the base cost to get a selling price.

Other costs

Some more cost terminology:

- Fixed costs are costs that do not vary in proportion to the quantity of output (more or less within a certain range). Usually this includes the upfront cost, any insurance, depreciation charges.

- Variable costs are costs that vary in proportion with the quantity of output, i.e., the variable cost is a function of the output .

The total cost is the sum of the fixed costs and the variable costs.

The average cost is defined as the ratio of total cost to quantity of output. It’s a unit cost, so it’s more useful for pricing decisions.

The marginal cost is how much 1 more unit will cost, or how much 1 unit reduction will save. It’s defined by the derivative of the cost function with respect to the output quantity. It’s more useful for engineering decisions.

Analysis

The most optimal operating point given two variable resources is to operate them where:

And . This gives us a linear system of 2 equations which we can solve for , the most optimal operating point.

This might not always be possible (only possible in theory). For example, some resources may be subject to constraints on how much they can produce.

- If , i.e., the capacity is constrained on one plant, then we operate plant 1 at max capacity, and the other plant will pick up the slack. and .

- If , then we have the same situation as above.

- If both capacities are constrained, then we operate both plants at max capacity. We can’t meet the demand.1

This gives us another way to find the sale cost of an item:

Financing costs

Future costs are any costs that may occur in the future, like O&M costs or disposal costs. The main implication is that future costs must be estimated, and thus are uncertain or subject to error, and thus introduce risk into the project.

Opportunity costs are the cost of foregoing the opportunity to earn a return on investment funds.

change in MC/AC often results in a discontinuity — for ex. overtime pay for employees minimum acceptable/attractive rate of return (MARR) — minimum rate of return that the project must take on to be acceptable

Footnotes

-

“Import the rest?” - Mike Xue ↩