Bitcoin is a decentralised digital currency system. At its core, it decentralises the computation and removes the need for a central authority (like a central bank or big tech company) to curate your computation for you, by enforcing cryptographic proof to make transactions secure.

Design

Nodes in the Bitcoin network are able to join the network at will: it is an open membership network without a single administrative control. Bitcoin implements a state machine replication consensus protocol while providing Byzantine fault tolerance, and it assumes nodes are untrusted (and can spoof their identity) and some may be malicious.

Why not PBFT? This requires a leader and a known number of nodes. Bitcoin essentially has the opposite of this. It would be easy to diverge replicas if a malicious person decided to flood the network with malicious nodes.

Transactions

Bitcoin follows the UTXO model, for unspent, transaction, output. The core idea is simple:

- Let be the th output of the th transaction.

- Suppose the sender has 10 BTC, and wants to send 6 BTC to the receiver. This is all with respect to some transaction ‘s coins to another transaction .

- They send 6 BTC to the receiver, and 4 to themselves.

A transaction will be between in the network, with both the sender’s signature and receiver’s signature. This has the property of non-repudiation, that the receiver is the only one that can decrypt the message (i.e., no stealing!).

- Transaction:

T = [pub(receiver), num_btc, hash(Tx), sig(sender)] - Signature:

sig(sender) = E(pri(sender), hash(data))

In practice, this means that if we send from T5 to a new T6, the original T5 is marked as spent. Any BTC we send in the future must be from T6 instead (which is okay since we sent 4 BTC to ourselves).

How do we avoid double spending? We check the blockchain and reject the transaction that comes last in the total order.

This can be viewed with a transaction graph. Any “spent” transactions are internal nodes, and any unspent transactions are leaves.

When someone “owns” BTC, we mean that the user has a public key to which BTC were sent, and the user has a corresponding private key that authorises the user to send BTC previously sent to the user (any transactions). In other words, a Bitcoin wallet essentially has a database of all unspent transaction outputs, which is done by scanning the blockchain and all new nodes. The Bitcoin protocol only handles and verifies transactions, not the BTCs themselves! So it’s not possible to create a “fake” bitcoin.

Blockchain

Clients will send financial transactions to the network via flooding to a few connected peers (to ensure all nodes are aware of a transaction). Nodes will log transactions in a ledge (like a cheque book) called the blockchain. Each node will keep a replica of the blockchain. Nodes will agree on a transaction order in the blockchain (a consistent total order), and will agree about the number of BTC owned by each account. They also check the validity of each transaction.

The entire transaction history around 500-550 GB. But pruning techniques allow for storage requirements to be 5-10 GB in practice.

Transactions may arrive at each replica in a different order (so we can’t maintain a total order right away). Transactions are only ordered relative to other transactions within the same block (in a mempool, with other unordered, unconfirmed transactions). Miners select transactions from their mempool to include in a block that they’re attempting to mine. Each miner can choose different transactions and arrange them in a different order. Then, then the new block is broadcasted, this establishes the ordering of transactions.

This public ledger is essentially immutable (with the exception of new blocks). No node is able to modify or hide transaction entries once they’ve been committed to the log. This preserves the safety/trust of Bitcoin operations and prevents the ability to double spend under normal operation.

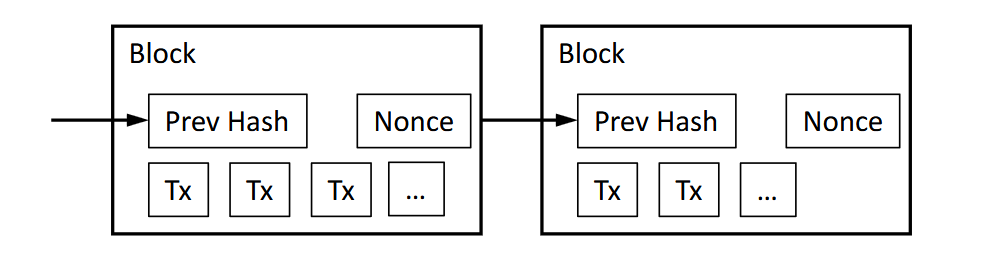

The ledger is made up of individual blocks (hence the name), just like a linked list. Each block is on the order of about 1 MB. It stores ~thousands of transactions. Each block has a few components:

- Hash of the previous block.

- This essentially links it to the rest of the ledger without using explicit pointers. If blocks diverge in some meaningful way (an intermediate block, that is), then the previous hash wouldn’t match.

- Hash of transactions (the root of a Merkle tree).

- And a random number used once (a nonce).

New blocks store new transactions, then is periodically linked to the blockchain (which is also flooded). It contains transactions since the previous block and is immutable. i.e., a new block is not initially linked to the ledger, but is after some time.

Mining

Since any node can add a block, Bitcoin achieves consensus by having a single “winner” node and other losing nodes. They do this by making it computationally difficult/hard to win in the first place in a process called mining.

To generate a new valid block, nodes have to find a nonce value such that hash(new_block) < target, some target difficulty set by the protocol. If the target has at least leading zeroes, then the number of tries is exponential in . This is because of the properties of cryptographic hash functions, which makes finding a satisfying nonce essentially random.

The mean time to mine a new block is ~10 minutes. The difficulty is adjusted by the protocol periodically (every ~2 weeks) to ensure that the mean time is roughly the same. More miners means a more difficult target. The variance is high because of how the mining task is defined, and some nodes will inevitably win before others.

When a new block is mined, it’s flooded to other nodes. These nodes (as well as the recipients of the transactions) then verify the validity of the block. This is essentially an NP-complete problem — finding a satisfying value is exponential, but verifying it is quite quick. If a block with a previous hash exists, then the block will be appended onto the ledger. And all transactions in the block are valid.

Formally, a transaction is valid:

- Its input transactions exist in the blockchain.

- Its inputs are unspent transaction outputs (UTXOs).

- Signature is by owner of input transactions.

The result are mining rewards:

- A block reward, which is paid out to the successful miner for each new mined block.

- This reward will halve every 4 years until being rounded down to 0, by 2140, which solves the problem of too many bitcoins. There’s a total pool of 21 million bitcoins, 19.8 million of which are currently in circulation.

- The first transaction in a block (coinbase transaction) is a reward to the miner.

- Transaction fees that are associated with transactions paid to the miner.

Implications

Consensus

How the protocol implements consensus is technically interesting, but it’s successful primarily because of financial incentives. Multiple blocks could be mined concurrently. This creates a diverging replica (a fork in the chain), and is the only instance in the Bitcoin protocol that can result in double spending.

At this point, nodes could start mining based on either node in the split. Once a new node is introduced to a split node, then nodes will switch to the longest fork when they see it and keep trying to extend it. This inevitably leads to lost work or lost transactions.

- Lost transactions (in orphan blocks) will have to be retried.

- Transactions in the preceding block will be confirmed now.

- In practice, Bitcoin clients will wait for the transaction to be committed as well as an additional block for safety, so that they know transactions won’t be overwritten.

- But many will be in the longest chain, so this is okay.

- Even if an equal number of nodes work on both nodes in the split, one chain is likely to be extended faster due to the inherent variance in mining.

This creates an economic incentive to compete and agree to use the canonical chain. This is essentially game theoretic, described by the Schelling point. One other problem is that it’s prohibitively expensive to make a non-canonical fork the canonical fork (i.e., if many nodes in the network collude). This is because you have to 1) grow the forked chain and 2) make it the longest chain. i.e., that you require >50% of the total CPU power of the network, i.e., that you spend more computational power than you get back in financial rewards.

Recall: blocks are immutable, since the nonce is specific to the current block. If you add a fake transaction, you essentially need to re-find the nonce, since the block now doesn’t have a valid hash value.

This aspect of the mining process is called proof-of-work. If most nodes are honest, then they will agree on the longest chain. Consensus is based on honest nodes having the majority of CPU power.

Centralisation of power

Bitcoin is so successful that there’s a lot of incentive to be a miner. Nowadays, miners have dedicated machines with ASICs (in the distant past, they used GPUs). This creates a very high barrier to entry.

Mining pools are where miners team up and split the rewards (more processing power; individual miners have very little power in the network). Both of these problems lead to a centralisation of mining power.

Performance

Bitcoin consumes a shit ton of power via mining (~0.65% of the world’s energy consumption, more than the country of Austria). One Bitcoin transaction (as a result of the mining) can consume 850 kWh (about a month of electricity for the average US household).

Its throughput is also not great:

- Average transactions per block is ~2-4k. 1 block is mined every 10 minutes.

- So a throughput of about 3-7 transactions/second.

- For comparison, Ethereum has about ~20.

- And Visa has about 2000, but can hit 20k at peak.

- And PayPal can support ~200.

As a Byzantine fault tolerant protocol, it makes a trade-off. Compared to PBFT, its throughput. latency, and energy usage are terrible, but it allows open membership in the network.

Value

- for fiat currency, value is backed by the government/central bank etc

- how do paypal, visa, etc work? they have their own private money, they issue dollar tokens, which is what we get. so it’s not real money. from fractional reserve system

- M0 money, much less than real money is — 8 T dollars

- derivatives - insurance of insurance of … in excess of 900 trillion - money that DNE

- “in my view, voodoo economics” - Veneris

- why everything collapsed in 2008

- bitcoin: able to transfer value without central authority

- very stable - no downtime since inception