In database theory, a transaction is an indivisible logical unit of work, where the program can perform multiple operations, represented as a single step. This is defined by the programmer with flags signifying the beginning/end of the sequence of code This essentially allows the system to run the transaction atomically, where the system will handle concurrent operations and add failure tolerance.

Basics

When the transaction is complete, it is ready to commit (which may or may not succeed).

- If it succeeds, then all transaction modifications have been written to storage, and results have been sent to the client.

- If it aborts (a failure), then all changes are undone.

- Generally aborts can happen for many reasons at any time before the commit, like if the transaction code issues an abort, or the system forces an abort (deadlock, or out-of-memory), or physical hardware problems (server crashes, disk failures).

Transactions afford us four key guarantees, called ACID. Note that the terminology in database theory slightly differs from systems terminology.

- Atomicity (in systems, failure atomicity) — the transaction executes completely, or not at all. Transactions will commit or abort changes, with the understanding that commits are final, and after aborts, the transaction can be retried.

- Consistency (not in the distributed system sense) — an application-specific guarantee that the transaction will only bring the database from one valid state to another, maintaining all database invariants (constraints, integrity, etc). This guarantee is controlled by the user.

- Isolation (in systems, atomicity) — no interference in database state between concurrent transactions, i.e., transactions should execute as a single indivisible step.

- Durability — once a transaction has been committed, all database state modifications have to be persisted on disk and be able to survive failures.

Atomicity and durability provides us guarantees of correctness under failures. Isolation gives us a guarantee of correctness under concurrency.

Concurrency control

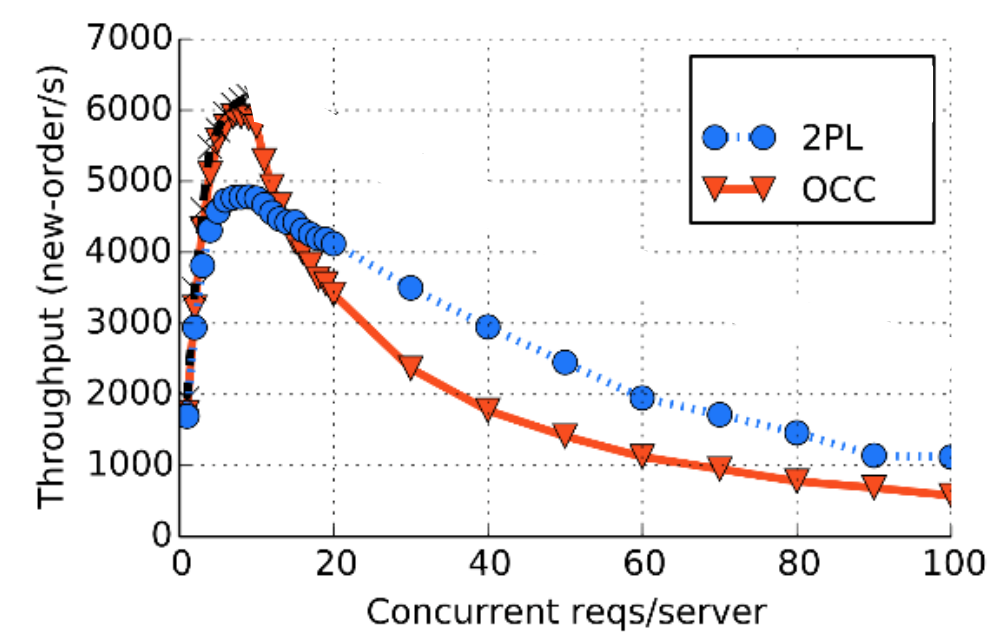

Two concurrency control schemes, both are essentially opposite of each other:

- Two-phase locking (2PL) has transactions acquiring all locks in a single phase, writing the data, then releasing them all.

- Optimistic concurrency control (OCC) accesses items without locking, as if they will succeed. Then, it checks whether reads/writes are serialisable only at commit time (i.e., acquire locks at the end).

The performance of transactions is not free. As more concurrent requests happen, both schemes eventually do poorer.

- serialisable — very strict definition, if some serial schedule

- if serial, then trivially it is serialisable

- 2PL rule

- growing phase

- shrinking phase — idea: cannot acquire any more locks after we’ve released one

- once a shared lock is acquired, it can be upgraded to an exclusive lock iff no other shared lock is held currently

- 2PL guarantees serialisability in this scheme

- db deadlocks

- application writers are 3rd parties

- can’t order accesses bc you’re not the one accessing — compare to OS, where application dev is assumed to be the same person locking/unlocking — so roughly consistent

see db internals pp 79

-

2pl downsides

- quite conservative, will acquire lock even when unnecessary

-

many modern db provide strict serialisability bc real-time constraints are easy to understand

-

atomicity + durability provided by WAL for single node transactions