In operating systems, a process is a single running instance of a program. There are some basic requirements for a process, namely that it must have a set of:

- Virtual registers (including program counter).

- And virtual memory (stack, heap, global variables). This includes the stack/frame pointers.

- And any file descriptors the process has open.

Since the process runs on the CPU directly, the OS kernel runs on a periodic interrupt timer (every few ms) that pauses the currently running process and returns control back to the kernel, called a context switch. Whether to keep running the same process or a different process is up to scheduling mechanisms.

This allows multiple processes to run concurrently. Modern OS can also run multiple processes in parallel.

Anatomy

Process control blocks contain information about the process, including: process state, CPU registers, scheduling information, memory management information, IO status information, among others. In Linux, this is done in a struct task_struct.1 Each process gets a unique identifier. In UNIX/Linux, this is a process ID (pid). In Windows, this is within a “handle”.

Each process control block also contains a file table, with file descriptors.

Process states

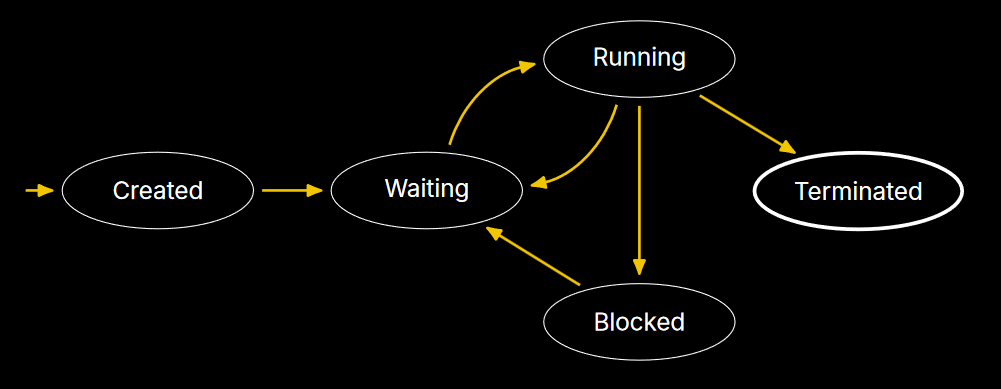

One property of processes is the state they’re in. These can be represented as a DFA within a state diagram.2 These states help the OS juggle multiple different “running” processes.

- Running — the process is currently executing instructions.

- Waiting — the process is ready to run but is not currently executing.

- Note that this means a process may not be fully finished executing when it’s moved to waiting. This is done via scheduling mechanisms.

- Blocked — the process is in the middle of some kind of operation that makes it not ready to run until another event takes place (for example, an IO request to disk or a syscall result).

- And some extra states that may depend on the operating system:

- Initial — process is currently being created.

- Final — process has terminated but hasn’t been cleaned up yet (called a zombie process in UNIX/Linux).

The OS will maintain a process list of processes with their state (blocked, waiting, and currently running).

On Linux systems, we have the following states:

On Linux systems, we have the following states:

Rdenotes running and runnable (running and waiting).Sdenotes interruptible sleep (blocked).Ddenotes uninterruptible sleep (blocked0.Tdenotes stopped.Zdenotes zombie.

The Linux kernel allows us to explicitly stop a process to prevent it from running, but we (as the programmer) or another process must explicitly continue it.

After the kernel initialises, it creates a single process init. This is responsible for executing every other process on the machine. It must always be active: if it exits, the kernel thinks we’re shutting down.

proc directory

The /proc directory represents the kernel’s states (not real files). Each directory in /proc that’s a number (a pid) represents a process. Within a process n’s directory, there’s a file status (/proc/n/status) contains the state of the process.

The process ID is unique for every active process. On most Linux systems, the maximum pid = 32768, and 0 is reserved. The kernel will recycle the pid.

Operations

All modern operating systems expose a process API, to create and destroy processes, to allow a currently running process to wait, some other miscellaneous controls (for example, a suspend then resume), and to get status information.

Creation

Processes load pieces of code/data only as they’re needed during program execution. The run-time stack and heap is also allocated by the OS.

TL;DR:

- Zombie process — child exits first

- Orphan process — parent exits first

Zombie processes wait for parents to read its exit status. Say a child process is terminated, but it hasn’t been acknowledged. The parent process may not necessarily read the child’s exit status (an error). In this case, the OS might cause an interrupt for the parent process to acknowledge the child.

Orphan processes require being re-assigned to a new parent. If the parent exits before the child, then init (or another special process) will take care of any child processes.

In Windows

In Windows, the program is loaded into memory and the process control block is created. The syscall CreateProcess() combines both of UNIX’s fork() and exec(), which creates a new process from scratch and executes it.

The new process doesn’t inherit resources from the parent. Note also that child/parent processes don’t exist in Windows.

In UNIX/Linux

In Unix-like systems, process creation clones the currently running process’ PCB into a new one (modelled as a parent-child relation). This reuses all of the information from the process, including variables. After this, each are functionally independent, and they can execute different parts of the program together or create more PCBs.

The only way to create a new process in UNIX is the fork syscall, which does the above: it creates a new process as a copy of the current one.

int fork(void)returns thepidof the newly created child process:-1denotes a failure,0in the child process,>0in the parent process.- Now there are two processes running with the same variables (copies of each other, won’t sync). Note that when the child process is spawned, it continues running from the same line as the parent process (because it’s an exact copy).

The execve syscall replaces the process with another program and stops the process.

The wait syscall is used on child processes, it essentially blocks program execution until the child process exits. Then it cleans everything up.

Footnotes

-

See the Linux source code. ↩

-

From Prof Eyolfson’s lecture slides. ↩